Rethinking Hardiness Zones

~ Choose the most ecologically beneficial plants for your native plant garden ~

Hardiness zones have long been the preferred method for plant selection and are primarily determined by a plant's ability to survive in certain climates. However, for those aiming to contribute to local ecology rather than merely ensuring plant survival, ecoregions present a more ecologically sound way to determine a plants’ suitability. Ecoregions take into account a diverse array of factors, including climate, soil types, and interactions with native species, offering a comprehensive framework for assessing the suitability of native plants. By shifting the focus from hardiness zones to ecoregions, gardeners can make more informed choices, benefit biodiversity and experience more success in the garden.

While this article is tailored to the Southern Great Lakes region, particularly Southern Ontario, the concept is equally applicable to all North American native plant gardeners.

Butterfly Milkweed (Asclepias tuberosa) is a popular garden plant but how do you know if it is native to your garden or not?

The problem with Hardiness Zones

Most gardeners have become accustomed to choosing plants based on hardiness zones. In the USA, hardiness zones are based off minimum winter temperatures. In Canada, they are based off a wider variety of abiotic factors including: climate, rainfall, frost-free periods, maximum snow depth, and more.

In both cases, these zones are helpful in telling us what plants from around the world will grow in our gardens which is useful for growing veggies, fruit trees and exotic plants as it confirms whether or not they will survive in your climate.

However, we grow native plants for more than just their beauty or ability to survive in our climate - we want to ensure that they will contribute to local ecology too. In this case, hardiness zones do little to nothing to tell us what plants will be beneficial to our cause - they just tell us if it will survive or not.

An obvious issue with using hardiness zones for native plants is that a plant from British Columbia can have the same hardiness zones as a plant from Nova Scotia, but these two regions have different native plants, animals and ecological communities. Plants from these two regions are not necessarily interchangeable in an ecological sense. Even if the two regions share a native plant species, they will likely have completely different genetic adaptations to specific local conditions, both abiotic and biotic.

An Ecologically Focused Alternative

On the other hand, a native plants’ suitable range is largely determined by the ecoregion it associates with, not the hardiness zone it will survive in.

Ecoregions are holistic categorizations of major components of native ecosystems, both abiotic and biotic, including: Average temperatures, climate, precipitation, underlying geology, soil types, plants and animal communities are all taken into account to produce unique ecoregions. Each region has plants and plant communities that are associated with it.

These regions are grouped together based on these wide range of similarities to help scientists, conservationists, and policymakers understand and protect the environment better. And now, it is being used by natural garden designers.

This holistic approach makes much more sense for natural garden designers to use rather than hardiness zones because they are based off the real-life plant communities and ecosystems that are found in each area. Another notable difference is that hardiness zones only use abiotic factors while ecoregions consider abiotic AND biotic. Essentially, they help us recognize which parts of the Earth have similar ecosystems and challenges, so we can take better care of our biodiversity.

I don’t believe this was ever intended for native plant gardeners but it makes sense for us to use because we are conservationists too!

Ecoregion Overview

You will notice three different levels of categorization, starting from level I (broadest), level II (more specific) then level III (most specific).

level I is too broad and it will have you planting palm trees in Ontario! Level 1 has its uses, but not for us.

Level II represents smaller ecological areas within level I. They are more specific but still fairly broad. As gardeners, I don’t believe we need to be as specific as ecological restoration professionals do. If you need a wider palette of plants to choose from in your garden or you are interested in assisted migration then you can use this map to expand your plant selection but otherwise, leave it alone.

Level III is the one we want as native plant gardeners. It represents smaller ecological areas within Level II regions. Level III regions are more detailed and enable the specific identification of local ecological characteristics and the development of more targeted plant choices. We can get even more local than this by looking at specific microclimates and habitat types but if we get too specific then we severely limit our plant selections in the garden!

After browsing these maps, you may notice that ecoregions don’t follow political boundaries. Plants and animals don’t, nor will they ever, acknowledge arbitrary man-made political boundaries. In reality, political borders are arbitrary and meaningless in this context because plant communities existed before territories or borders where established. Political boundaries, like hardiness zones, should not be used as a way to choose plants because it means we are categorizing them by parameters that have little influence on their preferred natural ranges and ecology.

It could be argued that political boundaries have DO have influence over ecology based on different approaches to conservation (or lack thereof) between different political jurisdictions, but this still doesn’t change the plants’ natural range or where they are meant to be growing.

In the end, the ecoregion level you choose will depend on how specific or rigid you want to be in your plant selection. It is important to note that ecoregions are not hard lines and that some fluidity can be expected. After all, we can’t expect plants to adhere to man-made lines, even if they are ecoregions! In other words, there is no problem with “borrowing” plants from neighboring ecoregions so long as you keep the bulk of your plant choices to your specific region.

How Do You Know What Plants Are Native To Your Ecoregion?:

Currently, the only way to tell what plants are best suited for each ecoregion is to get stuck into some research. I understand that this may add a new layer of complexity to the process, especially for new native plant gardeners, but it is seriously worth the time and effort to research what plants work best for your ecoregion.

By choosing plants this way, you will see much more success in both plant health, survival and wildlife value, because you know that these plants and animals are used to living together as a community.

Below I have given an example on how to research what plants are native to you.

Step 1 - Determine your level III ecoregion:

Find your level III ecoregion here.

By looking at the level III map, I have determined that my theoretical location in southern Ontario is considered to be in ecoregion 8.1.1: The Eastern Great Lakes and Hudson Lowlands. You can clearly see how this ecoregion, like all others, defies all types of political boundaries and stretches from Ontario into New York and Quebec.

Level 3 ecoregion maps are the native plant alternative to hardiness zones. Find where your garden is and determine your classification number.

Step 2 - Start a suitable plant list:

Next, go to the Ladybird Johnson Wildflower Center ( https://www.wildflower.org/plants/) website. This is a great place to start your research by plugging in the growing conditions you need plants for. This search will give you a list of plants that are suited to your site and it will tell you which province/state the plant can be found in.

We will use Butterfly Milkweed (Asclepias tuberosa) as an example.

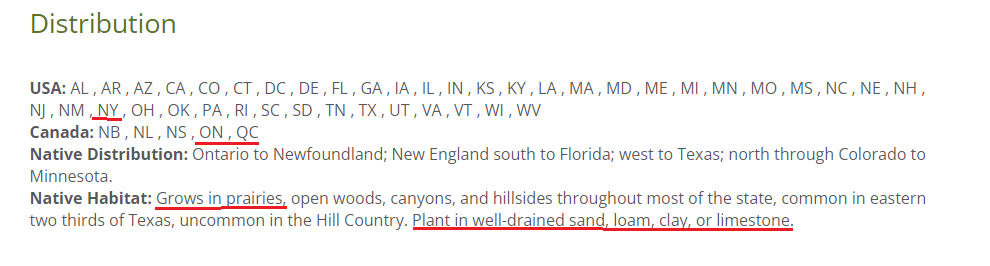

Below, you can see here that Asclepias tuberosa is native to my area on a provincial level. We know that we shouldn’t be choosing plants based on political boundaries but this give us a good starting point. Make a list of potential plants from this list and INCLUDE THEIR LATIN NAMES in the list because you will need them soon. Since my ecoregion covers parts of Ontario, Quebec and New York, I’ll consider Asclepias tuberosa to be appropriate thus far, considering these 3 jurisdictions are included in the distribution list.

The Ladybird Johnson Wildflower Center has a great plant search tool to begin your search. Pay attention to habitat preferences and make sure individual plants will be appropriate for your specific growing conditions (sun, soil, moisture, etc).

It is also important to pay attention to the habitat preferences of your plant. Despite Asclepias tuberosa being (potentially, at this point) native and appropriate for my ecoregion, it doesn’t mean its suited for the specific growing conditions in my garden. For example, Asclepias tuberosa likes full sun and dry soil so it won’t thrive in my moist shade garden. However, if my garden resembles a prairie or open woods ecosystem then Asclepias tuberosa makes the cut! Keep habitat preferences in mind while creating a list of potential native plants and only choose plants with habitat preferences that closely represent your site or you will be sorely disappointed when they don’t survive in your garden despite being native to your area.

Go here is my downloadable guide for helping you choose plants based on what ecosystem your garden represents.

Step 3 - Narrow it down:

Next, using the plants’ Latin name, look the plant up on the Biota of North America Program (BONAP) data base.

This site provides reliable county-level plant ranges for the U.S.A. and province-level ranges for Canada (Canada is far behind on this sort of thing and has less specific ranges, unfortunately). For Canadians, this can still be helpful if you ignore the political boundaries and compare these maps to our ecoregion maps. Look for any overlap between your plants’ range and your ecoregions range. For our example plant, you can see that our ecoregion covers parts of southern Ontario and crosses into New York.

BONAP shows that the range of Asclepias tuberosa includes the part of New York that overlaps with our ecoregion. This plant is clearly found naturally in our ecoregion, especially considering that the whole of southern Ontario is surrounded on three sides by this plants’ U.S. range. If your ecoregion is nowhere near the U.S.A, then skip this step. Since most Canadians live fairly close to the border, I assume this will be helpful for most of you.

Narrow it down by looking for where the plants’ range overlaps with your ecoregion. Canadians will have to make some assumptions here as the Canadian maps are not very specific.

Step 4 - Narrow it down with citizen science:

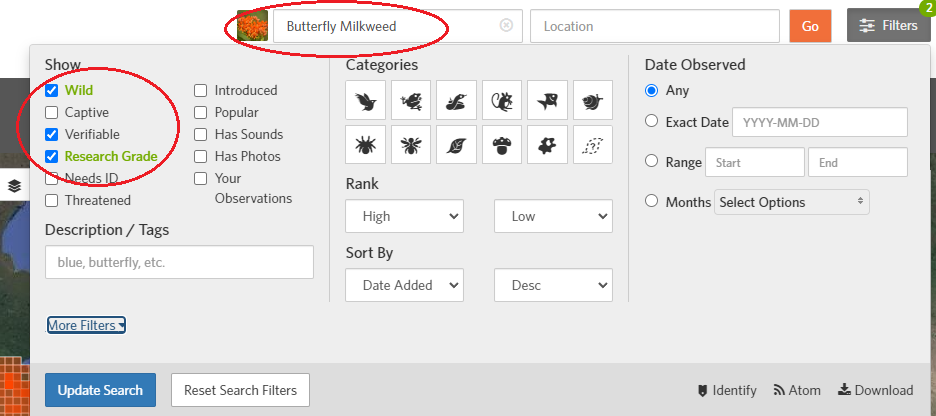

To narrow down our search even more, and confirm where a plant is currently growing in the wild, we will use the citizen science website/app iNaturalist (I prefer the website over the app for this part).

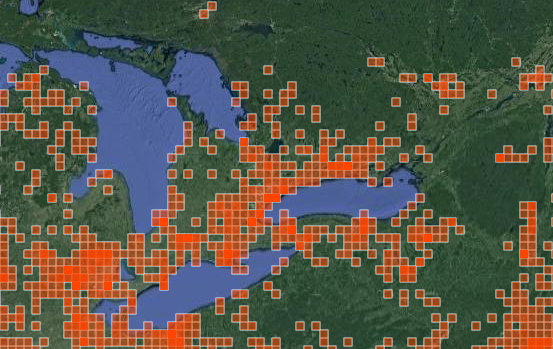

Run your plant through the iNaturalist search engine (use its Latin name) and filter your results to make them more reliable by choosing the “verifiable”, “research grade” AND “wild” filters. This will show you were your plant is naturally growing right now in the wild and will only include high quality, research grade results. It looks like Asclepias tuberosa is growing in suitable habitats throughout my ecoregion and if you look closely, its iNaturalist range loosely follows the boundaries of my ecoregion. In theory, you could jump straight to this step but keep in mind that the range of iNaturalist observations can include plants that were planted by humans or could have spread from gardens unknowingly. It is still a good tool to help us confirm our previous research and the more tools we use, the more accurate our results will be. When it comes to iNaturalist, I tend to ignore extreme outlier populations unless I know for a fact that it is a natural population.

Narrow down your iNat search to focus on confirmed wild plant distributions.

The search results: We can see that this map both fills in the gaps and confirms the results of our previous searches.

Step 5 (optional) - For the hardcore native plant gardeners

Great, so I am confident that Asclepias tuberosa is native to my location in ecoregion 8.1.1. To take this further, I can research which wildlife species this plant benefits and cross-reference this with where those wildlife species can be found in my region. If my goal is to support biodiversity then this is a logical step in the process to ensure that my plant will be supporting flora and fauna that are native to my area.

To do this, we must first research what wildlife associate with, and benefit from, Asclepias tuberosa. The best resource I know of for this is the Illinois wildflowers website. Look up your plant on this site and scroll down to “faunal associations”. Using iNaturalist, compare the faunal associations of Asclepias tuberosa with the range of these wildlife species. In my case, I notice considerable overlap with most, if not all of the species listed under faunal associations.

Diggers bees? Check. Leaf-cutting bees? Check. Monarch caterpillars? Check. Ruby-throated hummingbirds? Check. A variety of other insects that feed birds in my area? Check. It looks like the native wildlife in my area will benefit from this plant.

In other words, this plant is very relevant to my local wildlife and will be a valuable contributing member to local ecology in my garden. This method can also be used to determine ecological value when you are “borrowing” plants from neighboring ecoregions.

https://www.illinoiswildflowers.info/prairie/plantx/btf_milkweedx.htm

Additional Resources:

Native plant nurseries: If you really don’t have the time, patience or desire to do this research then the next best thing you can do is talk to your local native plant nursery and ask them what will work in your garden. Chances are that reputable nurseries will be willing and able to help you decide what is best for your garden.

Conservation authorities (Unique to Ontario): Many conservation authorities (36 in total) have planting lists suited to specific watersheds. These are very region specific and an excellent resource to use depending on what watershed you live in.

For example, Credit Valley Conservation: https://files.cvc.ca/cvc/uploads/2014/09/plant-selection-guideline-2014.pdf

Or Upper Thames River Conservation Authority: https://thamesriver.on.ca/watershed-health/native-species/recommended-trees-and-shrubs/

Special note on the Carolinian zone (8.1.2 Lake Erie Lowland):

Oldhams guide to Carolinian plants provides a detailed list of plants to choose from. Unfortunately, many of these plants aren’t available in nurseries but if you compare this list to what is found at your local native plant nursery then you’re good to go!: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Michael-Oldham/publication/317731067_List_of_the_Vascular_Plants_of_Ontario%27s_Carolinian_Zone_Ecoregion_7E/links/594b0567aca2723195de8ac8/List-of-the-Vascular-Plants-of-Ontarios-Carolinian-Zone-Ecoregion-7E.pdf